#KATRINA10 – Holding the Loss and the Grace: Remembering Ten Years Later

Nine years ago, I was talking with an elderly woman on the stoop of her ranch house in New Orleans, her home for 50+ years. She and her husband had raised their kids there, and she lived there after her husband died a few years earlier. Two or three days before Hurricane Katrina, she’d fallen and broken her hip and was in the hospital as the storm headed for the city, and her son had offered to stay at her house with his dogs and hers. When the levees burst, her son and the dogs all drowned. The search and rescue teams had discovered and removed his body, but had left the dogs and the lifetime of flooded belongings behind in the Louisiana heat. Almost a year had passed. Episcopal volunteers were clearing it out.

I had driven to New Orleans in late 2005, a few months after Hurricane Katrina, very much an average, mildly-engaged young Episcopalian. I had graduated college in Iowa a few years earlier, and had bounced around rural parts of the state as an unsuccessful political organizer. I was looking for a place to be helpful and to bide my time until maybe I’d go to law school, and I’d heard my cousins’ priest announce a trip gutting houses in New Orleans leaving the day after Christmas. It was exactly that simple – work I knew nothing about in a place I knew nothing about, going because the dates worked well on my calendar.

I arrived to a city still very much in complete crisis: almost no street lights, very little electricity restored, no public schools open, 80% of the housing stock uninhabitable, universities relocated, restaurants serving one dish on paper plates because they couldn’t get the kitchen crews back. Evidence of the flood’s destruction was everywhere – and would continue to be for years – having flooded homes slowly enough in some areas to leave folded laundry on ruined mattresses, or so fast in others to have piled houses and cars on top of one another.

I started working out of the Chapel of the Holy Comforter in Gentilly with the wonderful Rev. Roger Allen. He was newly ordained and almost all of his parishioners, including he and his wife, had lost their homes. But the church hadn’t flooded and had the only flush toilet in 30 square miles. My team from DC started helping gut homes for this congregation, and when the other volunteers from my team left, I stayed behind and began working for church members’ friends, neighbors and the random folks who drove by and asked for help for their great-aunts or whoever. I got hired by the Diocese of the Louisiana to continue the work coordinating teams to gut (and eventually rebuild) homes, through a grant with Episcopal Relief & Development as part of the larger diocesan Office of Disaster Response.

Our program prioritized folks who were struggling most, folks for whom being unable to take care of clearing out their house was certainly not their biggest problem, but for whom tangible evidence of progress might give them the emotional energy to tackle other things. Other gutting programs – perhaps understandably – focused on house gutting as a housing program, and vetted cases through a housing lens: did this person want to move home? Would they have the means to move home? Did they have a plan for their recovery? We looked at the problem through more of a pastoral lens, aiming to serve folks who had no idea if they’d be able to move home ever again, but might feel a tiny bit better if we could find their wooden Last Supper statue or daughter’s brass shoe or husband’s purple heart.

In New Orleans over the next few years, I think I saw what the Body of Christ looked like, and smelled like and sobbed like – both beautiful and damaged – in that woman on her stoop and in the volunteers working inside and in similar scenes repeated hundreds of times over. Since then, I’ve thought a lot about how we, as a church, are doing being the body of Christ in the world today. When one part is suffering or injured, do we try to walk it off, ignore the pain and hope it goes away, or do we tend to the wounded part with respect and loving-kindness until it is healed?

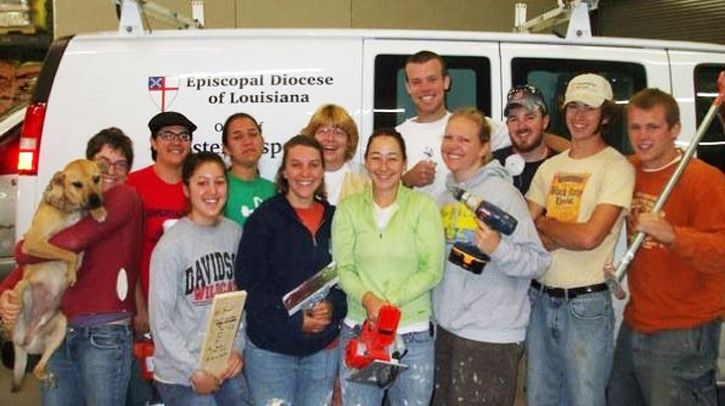

The Body was hurt in New Orleans, both by the storm, but also by generations of poverty, racism and governmental neglect. Our broader church body saw the immediate need and responded, with funds and volunteers arriving by the thousands: school trips, adult mission crews, bridge clubs, coworkers – some for a day or two, some for a year, leading crews and working more closely with the homeowners. We sorted sodden belongings and removed mountains of moldy clothes and took down wet sheetrock and paid for subcontractors and hung walls and installed floors and planted flowers. We made so many phone calls. We donated and we sweated and we did boring office work. We prayed with folks and for them, and we sat with them while they cried.

In working with these folks and in hearing their stories, both about the storm and about their lives before the storm, I saw the ways that systemic failures, systemic problems in our broader Body – in our schools, in our criminal justice system, in our disaster response structure – had and have real impact on real people. We all had a role in creating a system where the levees failed in New Orleans and drowned its residents, where people were too poor to be able to evacuate, where the public schools hadn’t functioned well for generations and illiteracy was so high. And we all have a role in the recovery, both with shovels and screw guns, but also in working to create justice in our communities, in our nation and throughout the whole Body.

Ten years after Katrina, I think there can be a tendency to turn these anniversaries into simply celebrations of our good work. It’s true that meeting the people I met in New Orleans in the years after the storm changed my life and, in many ways, changed our church for the good. We did good work. But I cringe at the idea that Katrina ten years later is that saccharine – that it’s told as a nice transformation story for me, the white Northern volunteer who made a career out of the suffering in the storm’s wake. Katrina’s anniversary should be a commemoration of the nearly 2,000 people killed and a call to action to prevent the systemic failures that led to their deaths. We need to hold on to both the loss and the moments of grace.

I had arrived to New Orleans fond of the Episcopal tradition I’d grown up with, and I left transformed and inspired and sobered. I feel so called to this work, both within the church but also within the broader Body, and will continue to look for ways that the cracks caused by disasters can be openings to step out of our normal patterns and create change.

Holy Women, Holy Men provides this collect for anniversaries after disasters:

God of steadfast love, who led your people through the wilderness: Be with us as we remember and grieve. By your grace, lead us in the path of new life, in the company of your saints and angels; through Jesus Christ, the Savior and Redeemer of the world. Amen.

Be with us, we pray, as we remember and grieve the nearly 2,000 lives lost and millions of lives changed. Lead us in the path of new life, one toward wholeness and love and justice, as a nation and as a church.

Take a look inside Katie’s experience in New Orleans with this photo essay:

——————–

Katie Mears is the Director of Episcopal Relief & Development’s US Disaster Program.

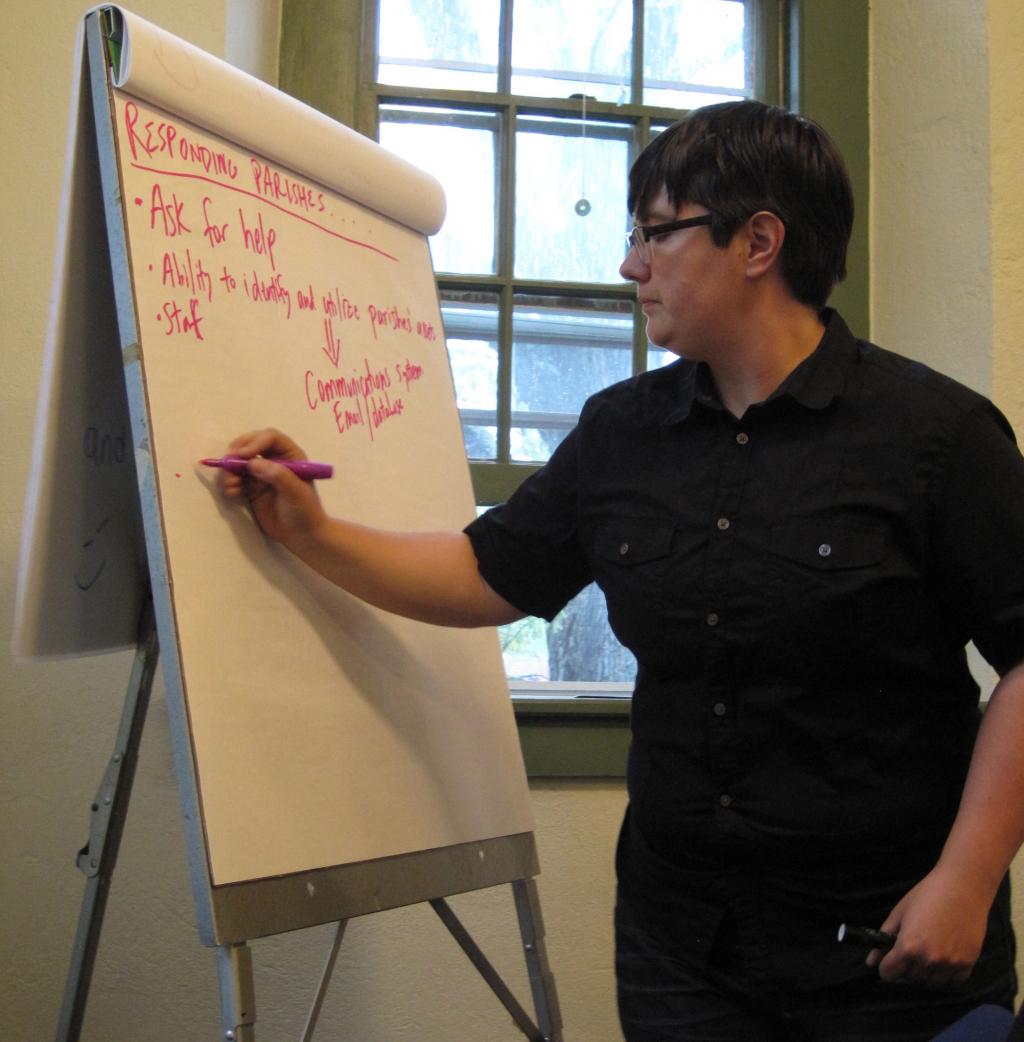

Images: Top, The inside of a partially gutted home. Middle, A volunteer laying tile in a homeowner’s house. Bottom, A team of interns from Kenyon, Grinnell and Ohio Wesleyan.

Healing the world starts with your story!

During the 75th Anniversary Celebration, we are sharing 75 stories over 75 weeks – illustrating how lives are transformed through the shared abundance of our partners and friends like you! We invite you to join us in inspiring our vibrant community by sharing your own story!