Caring and Compassion for People Living with HIV/AIDS

By Faith Rowold and Ximena Diego.

——————————

Today’s feature story explores the vital work of our partner Siempre Unidos. It started with an Episcopal priest in Honduras who recognized a need in his community and found a way to offer care and compassion for people living with HIV/AIDS. Eventually, the work expanded to target commercial sex workers and other marginalized members of society through Project Siloé. This unique outreach program trains counselors to encourage safe health practices and help people live with dignity and hope. This post was originally shared on World AIDS Day. Join us in remembering lives lost, supporting survivors and celebrating this important ministry.

One Friday evening in late January, as the sun sets in San Pedro Sula, Honduras, the street that borders Parque Central continues to buzz with weekday activity: a merchant offers discounts from a bullhorn; men in suits and women in button-down shirts rush past him; construction workers put the final touches on the bleachers set for tomorrow’s mayoral inauguration.

During the day, this downtown corner appears entirely ordinary. But in a few hours, it will become one of the city’s notorious red light districts, and the workers taking on the night shift are already here, almost unnoticed. Dressed in miniskirts or shorts, tight tops and flip-flops despite the chill in the air – more than a dozen women wait for clients. Four men in their early 20s are even less conspicuous. They chat in groups, casually sitting on benches or standing under the long shadows of the Spanish-colonial Cathedral.

Episcopal Relief & Development’s partner in northern Honduras knows this corner quite well. For the past 18 years, Siempre Unidos has provided life-saving medical care and emotional support to those impacted by HIV/AIDS and has worked on many levels to curb the nationwide epidemic. Its fastest-growing outreach program, Project Siloé (pronounced see-low-eh), targets the most vulnerable, stigmatized members of society: commercial sex workers. Siloé‘s counselors visit sites like this one every night from Tuesday through Saturday to promote safe sex practices, monitor the participants’ health and offer advice.

When three Siloé counselors wearing jeans and matching yellow t-shirts approach several women seated on the curb, the women stop chatting and stand up to greet the counselors with a hug and a kiss on the cheek.

Yolany, a cheerful 32-year-old counselor with shoulder-length curly hair, dark-rimmed glasses and an infectious smile, spends the next half-hour catching up on the latest news, addressing the women in small groups and then holding one-on-one conversations. Like her colleagues, Yolany talks to the sex workers with the intimacy of old friends: standing in close proximity, keeping eye contact, holding a hand, laughing. “They know they can ask anything,” she says. “We don’t judge them; we are here to support them.”

These informal meetings with staff ensure that Siloé participants have enough condoms and understand why it’s paramount they use them – no matter how much money they’re offered. While speaking, Yolany drills them on how to negotiate the use of protection with their clients.

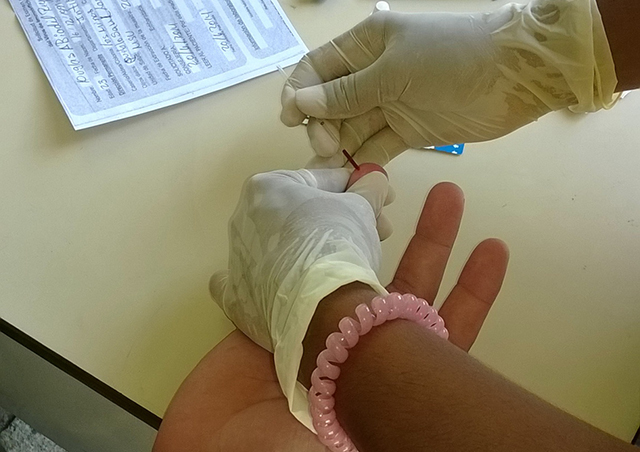

Through these periodic conversations, and with a free, confidential HIV test administered every three months, Siloé tracks the health and well-being of over 500 commercial sex workers – about 300 women and 200 men. Since the program started more than eight years ago, participants have had zero new infections. This kind of record keeping serves a functional purpose, but also validates the importance of each life, nurturing each person’s sense of self-worth and letting them know that they are being counted and cared for.

Helping commercial sex workers stay HIV-free and tracking their health is only part of Siloé’s mission. “We want them to realize that what they do doesn’t define them. This is something they are doing to feed their families,” says Yolany, explaining that most of the women are single mothers. “When we ask them, ‘Where do you see yourself 10 years from now?’ and they realize they don’t want to be doing this, they start thinking what else can they do.” Yolany wants to give them the tools they need to take control of their own lives.

Dozens have taken Siloé’s workshops on jewelry making, baking and sewing – learning new skills that allow them to find an alternative source of income. Some participants are now cleaning houses, selling necklaces or homemade baleadas (Honduran snack of tortilla with mashed beans). One participant went back to school and is now six classes shy of becoming a lawyer. “She wants to work with victims of domestic violence,” Yolany explains.

Yolany can relate to the women and men in this program. She knows how it feels to be rejected by society and all alone. “Siloé changed my life, too. Not just theirs.”

With roughly the population of New York City, Honduras has over 26,000 adults living with HIV/AIDS. The lead organization coordinating the global response, UNAIDS, estimates the national infection rate at 0.45%, with a much higher prevalence among commercial sex workers (6.7% in San Pedro Sula) and the Garifuna population (over 4%). To the Rev. Pascual Torres, founder of Siempre Unidos, these numbers don’t even begin to tell the social repercussions of the epidemic.

As a newly ordained Episcopal priest, Torres started visiting patients diagnosed with HIV in hospitals in the mid-1980s. “It was the time of paranoia,” remembers the 56-year-old Torres, a former lawyer. “People didn’t understand how the disease was spreading.” All he could do was accompany patients no one wanted to see, touch, or hear.

Deeply moved by the suffering and discrimination he witnessed, Torres made it his mission to bring comfort and dignity to those affected by HIV/AIDS. “I just wanted to alleviate human suffering,” he says. But people around him rejected the idea of building a ministry around this community. “Even within the Church I was criticized. ‘Why these people?’ they would ask – at the time, the disease was associated with homosexuality. ‘The Church shouldn’t be with these kind of people.’” But Torres disagreed. “If the Church is not with the people who live on the margin, with those who are rejected by society, where else should it be?“

By 1995, Torres had rented a space to host regular self-help group meetings for people living with HIV. “Siempre Unidos started with four people and a dream,” he likes to say. Now, “thanks to generous donors and several partnerships,” his ministry oversees three comprehensive health centers that treat more than 600 patients in San Pedro Sula, Roatan and Siguatepeque. “We reach well over 1,000 people if you count the patients’ families.”

The clinics provide life-saving medications that public hospitals often lack, and a holistic approach that includes psychological counseling, periodic testing and a support group that meets twice a month. His staff of 42 people includes physicians, nurses, counselors, technicians, psychologists and a sociologist who oversees the outreach programs.

On the prevention front, Siempre Unidos runs programs to educate at-risk populations in penitentiaries (where inmates are also periodically tested) and in high schools and universities, as well as in the red-light districts. When counselors first started approaching commercial sex workers in nightclubs, bars and parks, Torres recalls that many “didn’t know how to use a condom, and they wouldn’t seek medical attention for fear of discrimination.”

But when counselors witnessed that women, men and transgender sex workers were constantly being harassed, wrongfully detained and physically abused – both by authorities and civilians – Siempre Unidos expanded Siloé’s scope of work. “When our partnership first started [in 2007], our goal was to work towards increasing awareness and promoting HIV/AIDS prevention behaviors,” says Kellie McDaniel, Program Officer for Episcopal Relief & Development. Now, it also works “to document gender-based violence, discrimination and human rights abuses suffered by commercial sex workers,” McDaniel says.

Indeed, Siloé has compiled the largest, most comprehensive database of commercial sex workers in San Pedro Sula, including reported assaults and other crimes against them. The group also hosts periodic roundtables in which a newly formed coalition of commercial sex workers can talk face-to-face with military police personnel and members of the Department of Justice.

Now, with the implementation of a Human Rights Observatory that follows up on cases of abuse and encourages victims to press charges, participants are standing up for their rights. “More cases of violence are being reported to the authorities,” says McDaniel. “And Siloé has strong relationships with local agencies that help them find justice.”

The growth of Siempre Unidos and its impact on HIV/AIDS in Honduras has happened through a combination of high-level partnerships and grassroots organizing. At the community level, compassionate and knowledgeable counselors like Yolany provide tools and support to help vulnerable people keep themselves healthy and safe. However, not everyone has Yolany’s personal understanding of the fear, anxiety and stigma that can be associated with HIV.

Yolany was 19 when she was diagnosed with HIV. She was married and had a 5-year-old daughter and a source of steady income working at a maquila (factory). But when a visit to the doctor prompted blood work and a nurse dismissively told her she was HIV-positive, her world collapsed from under her feet. “She told me I would die soon,” recalls Yolany, “because I had AIDS.” Yolany didn’t believe the nurse – she didn’t understand how it could be possible.

But further testing revealed that Yolany’s immune system was not yet severely compromised. She didn’t need medications until three years later. At Siempre Unidos, she started receiving psychological counseling and began attending its support group meetings. She learned to lead a healthy lifestyle. “I also began to study everything I could about HIV/AIDS.”

The more she learned, the more determined she became to help others. “I decided to fight for my life and prevent people from having to go through what I went through,” says Yolany, who became a certified counselor and technician for rapid HIV testing.

When Father Torres decided to start Project Siloé and hire staff for the program, Yolany was one of the first people who came to mind. “She was so committed to helping others and knew so much already.” Now, she is the one saying, and proving, that being HIV-positive is not a death sentence.

Today, Yolany is also the proud mother of two daughters, ages 16 and 5, and lives with her long-time supportive partner. She still attends Siempre Unidos’ support groups twice a month. “I’m very fortunate,” she says. “I’m supporting my daughters doing work that I love.”

Faith Rowold is the Communications Officer at Episcopal Relief & Development.

Ximena Diego is a bilingual writer based in New York City whose work has appeared in Latina, Library Journal and Catholic newspaper Nuestra Voz.

Images 2 and 5 by Ximena Diego; all others by Corey Eisenstein for Episcopal Relief & Development. 1, 2 and 7, Yolany and colleagues. 3, Yolany. 4 and 6, Support group at Siempre Unidos. 5, Getting tested.

Healing the world starts with your story!

During the 75th Anniversary Celebration, we are sharing 75 stories over 75 weeks – illustrating how lives are transformed through the shared abundance of our partners and friends like you! We invite you to join us in inspiring our vibrant community by sharing your own story!