Working Together in Response to This Year’s Not So Little ‘El Nino’

It’s pouring rain outside in New York as I write this in late March. We are nearing the end of a winter where we saw more rain than snow, and many days like this past Christmas, where it was so warm we could sit outside and relax – with no coat! Not exactly typical weather for New York.

While I enjoyed the warm days – I couldn’t quite feel at ease – knowing that this year’s El Nino climate episode was bringing changes to weather patterns around the world where we work, some of the them less welcome.

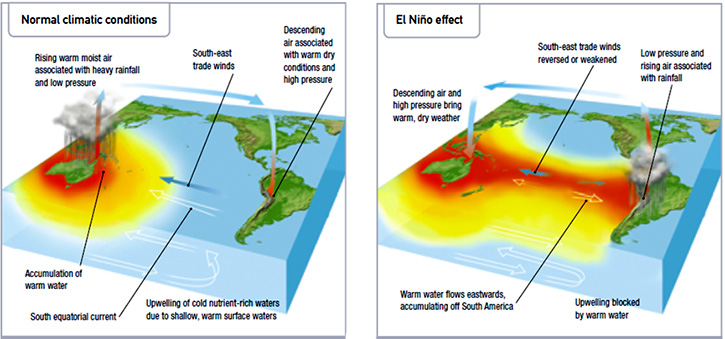

The 2015-2016 El Nino, which began around March of last year and will continue through 2016, was predicted. However, it is more difficult to predict the expected intensity, and so it is just in the past few months that it has become clear that is year’s El Nino isn’t so little – in fact by many measures it is the most intense in the observed records dating back to 1950.

El Nino episodes occur every 3-5 years, and result in changes in rainfall patterns globally, therefore leading to the potential of either drought, or heavy rains and flooding – both of which can hugely disrupt the seasons of the small family farmers we work with.

Since late 2015, we have been using our extensive network of local partners to check in on what is happening locally in different regions. Encouraging them to listen to local forecasts, and act accordingly to prepare – the earlier the better.

Through these conversations, we’ve learned that two regions – Southern Africa, and Central America, are particularly concerned. Both of these areas experienced very low rainfall last year, and so household, community and national stocks of food are low, and families may have already depleted their savings. As the drought continues in these areas, it is becoming clear that the 2016 harvest will be much lower than average.

In Zimbabwe, for example, many areas are experiencing extreme heat, a very late onset of rains or little to no rainfall. As they shared with us: “Unfortunately some farmers had dry planted their crops anticipating rains to start in November, that would lengthen their season, which is usually beneficial in places of minimal rains. As long as it does not rain the planted seed remains dormant in the ground and will germinate when it rains. Given the high temperatures experienced farmers are seeing that their seed will likely not germinate.” As of March, much of the country had received 50% or less of expected rainfall – and up to 4 million people are vulnerable and in need of support to meet basic food needs.

And in Nicaragua, the drought is expected to cause up to a 60% decrease in maize production, and an 80% loss for beans, with hundreds of thousands of families affected. This type of widespread drought is also having an impact on the environment which these families rely on to produce food, increasing the risk of soil erosion, decreased water quality, loss of biodiversity and an increased risk of forest fires.

During these conversations, we wanted to use the knowledge in our Episcopal Relief & Development network, to support farmers to be able to prepare, adapt, respond, and recover from, this, and other ongoing climate challenges. We collected and documented the strategies they are using with communities in response to predicted or current droughts and heavy rains, and compiled them into an El Nino Adaptation tool, to add to our ‘Pastors and Disasters’ toolkit – for community-based disaster risk reduction and management.

Tips from our network including everything from using compost and increased tree cover to improve soil water retention, to negotiating animal grazing management before drought conditions peak, to connecting farmers to local social protection options. The exciting thing for me was to see all of the ideas come together – and in combination form a list of options which could be successful in Zimbabwe, or Nicaragua, or India – in communities which would otherwise not be able to share thoughts with each other.

The other suggestion we heard from them was a call for others to be working together in the same way. Government agencies in the affected countries have the ability to strategically lead at a national level, and other food security stakeholders, including donor agencies, NGOs, other faith-based organizations, need to communicate, share and act together as much as possible in order to best support communities through this very ‘not little’ challenge.

—————————————–

Sara Delaney is a Senior Program Officer at Episcopal Relief & Development

Sara Delaney is a Senior Program Officer at Episcopal Relief & Development

Image Captions: Top, “Dry season bean production in drought-affected Nicaragua” by Neil Palmer (CIAT) is licensed under CC BY-SA 2.0. Middle 1, Atmospheric and ocean conditions in the Pacific region in normal climatic conditions and El Nino years. Middle 2, Shona farms in Zimbabwe by Ulamm has been released into the public domain. Middle 3, “A coffee farmer dries his arabica beans in Nicaragua” by by Neil Palmer (CIAT) is licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 2.0. Bottom, “Indian Navy relief efforts during the 2015 floods in Chennai” by Indian Navy is licensed under CC BY 2.5 IN.